© Official Site Of 555th Parachute Infantry “Triple Nickle”. 2008

By Walter Morris

It was a beautiful summer morning on August 25, 1945. The sky was a light blue and the bright sun was just beginning to rise above the horizon. It was

six o’clock and I was standing in the open door of our C-47 transport plane, which was flying at an altitude of 1500 feet and 150 miles per hour.

I was a Second Lieutenant in the 555th Parachute Battalion of the United States Army, an all-African American Battalion. I had one officer and 34

enlisted men under my command and we were on our way to fight not the Germans nor the Japanese, but a “raging forest fire” in the Mt. Baker

National Forest of Washington State. Our mission was classified by the Army as “Operation Firefly.” One might ask why combat trained paratroopers

were preparing to jump into a forest fire instead of the fields of Germany; after all, this was 1945 and the United States was at war with Germany. The

answer was simple: In 1945, the Army, along with the rest of the nation, was a segregated society. Black soldiers or “colored soldiers,” as we were

referred to in the 40’s, were relegated to serving in menial units such as truck drivers, port companies (loading ships), mess halls (waiting on tables)

and guard duty - so, how did we have Black paratroopers? That thought came to mind as I gazed out the open door of our plane. Why, I asked, was I

standing here on my way to a dangerous mission that could possibly get me and my men killed? Why should I die for a country that thought so little of

me and my people?

My thoughts went back to the year 1943. I had just washed out of Infantry Officer Candidate School at Ft.

Benning, Georgia. The Review Board suggested that I select one of three service outfits on the Post and

reapply to the School after three months. I had completed twelve of the thirteen week course. I had almost

made it. I selected the Service Company of Parachute School; a school that trained white soldiers to

become Army paratroopers.

It was early spring in 1943 when I reported to the Service Company and within a few weeks I had this idea

that I could change the Company from a bunch of bored Black men doing guard duty for the properties of

the school into something better. The tour of duty began at four p.m., when the white students left the

field, and ended at eight a.m. when the students returned. Day in, day out. When not on guard duty, our

company slept all day. Morale was at its lowest ebb. Having just come from O.C.S., I thought I knew how

to lead men; after all, I had just missed becoming an officer in the United States Army by one week. I

wrote out a plan with changes in personnel and presented it to the Company Commander. He reviewed it

and approved it. The Company Commander was a paratroop school failure and was on a list to be

transferred overseas. He spent most of his time in the Officers Club and could care less what happened to

the men or the Service Company. The men who were running the company were all in an acting position

in rank - Acting First Sergeant, Acting Supply Sergeant, etc. When I introduced my plan of operations, no one really objected. Their attitude was - who

cares; what difference can it make?

I began the plan by moving certain people from position to position: the First Sergeant was made Supply Sergeant; the Supply Sergeant became one of

several Platoon Sergeants. I made myself First Sergeant. Things began to shape up slowly. I introduced my idea of having our men imitate the white

students as they went about exercises. As we were around them all day, we could do (or try to do) everything they did, with the exception of jumping

from the 250 towers or planes in flight. So it was that each day after four o’clock when the white students left the field, the “colored students” took over.

Within weeks you could see the changes in our men: shoes shined, clothes pressed, haircut and combed - morale was up. They had found that, given

the opportunity, they were just as good as the white students; no better but no worse.

There was something else that struck me. It was customary for soldiers to greet each other with “Hi, #$%@#,” or to say to a friend as they went to mess

hall to eat: “you can go in first, #$%@#.” This was not said in anger, but more as a habit. We Non-Coms decided to change that habit. We started giving

company punishment for any man heard using that phrase. The punishment prescribed was for the soldier to carry on his back the baseplate of an 81

millimeter mortar as he walked around the company area. When you saw a soldier

carrying a baseplate on his back, you knew he was being punished for saying “the

phrase.” It wasn’t long before the men solved the problem. They began to address each

other by “Baseplate,” i.e., “Good Morning Baseplate.”

As my mind returned to the plane and 1945, I noticed the light over the door had turned

red. This meant to the Jump Master (the person in charge of getting the Paratroopers out

of the plane when it reached the Drop Zone) that we were twenty minutes from the forest

fire. The palms of my hands were damp; it wouldn’t be long. I checked my equipment;

made sure I had my cigarettes where I could get to them.

I thought back again to 1943 - Ft. Benning. One day, as we were “doing our thing,”

(pretending to be students) we were observed by none other than the Commanding

General of the Parachute School, General Ridgley Gaither. He was a southern soldier

who had the reputation of being as tough as nails and just as straight. The General was

very impressed with our performance and, within a few days, he sent for me to come to

his office. To my surprise, he told me of a highly classified order. The Army had

authorized the activation of the 555th Parachute Company comprised of all African

Americans, or as the orders read “all Colored troops.”

General Gaither asked me if I would accept the position of First Sergeant of the

Company. Needless to say, I accepted. Months later, during December 1943, we were a

company of officers and enlisted men qualified to jump out of C47’s. What General

Gaither did not say and I later learned, was that it was the hard work of African Americans

like A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, General B.O. Davis and the Black Press that

convinced President Roosevelt, under threat of a March on Washington, to dramatize the

need for more jobs in the defense plants and to accept Black men in the Parachute

School. This was twenty years before the famous 1963 March and the Dr. King “Dream”

speech. That March was also organized and staged by A. Philip Randolph.

After we received our wings, we helped train six Black officers to receive their wings. To

fill the quota for a separate company, the Army requested African American volunteers

throughout the United States and the European Theatre. There was such overwhelming

response to the request that we soon had enough qualified jumpers to fill the quota. It was

then that the decision was made by the Army to make the Company a Battalion. Because most of the cadre came from Fort Huachuca, we became the

“Triple Nickles” in honor of the Buffalo Soldiers. General Gaither recommended that I attend Officer’s Training School at Fort Benning. I did so and

graduated with the rank of Second Lieutenant on November 8, 1944. As I approached one of my Sergeants wearing my shining Second Lieutenant

bars, he snapped to attention, saluting me, and in a voice only I could hear, said “Good morning Baseplate.”

Soon I was sent to the Adjutant General School in Ft. Sam Houston, Texas, for six weeks’ training for Battalion Adjutant. When I returned to Camp

Mackall, the Battalion was preparing to move west on a highly classified assignment. Surely, we thought, this well-trained unit of 400 plus men was

going to fight the Japanese. No such luck; the luck came to the Army. Since no Field Commander in Europe or the Far East wanted “colored troops”

mixing with their racist white troops, the Army was stuck with us. As General Mark Clark stated, “We have a war to fight and win; I don’t need the added

war that would be fought between our own men if I have to integrate the soldiers.”

This is where the Army got lucky. The Forest Service asked for help in fighting the many fires that were spreading throughout the West Coast. The fires

were due in part to incendiary bombs carried by balloons on the trade winds from Japan toe the US coast - from Washington to Oregon to California

and even Montana. These fire bombs landed and started fires on impact. These balloons were made of a special laminated mulberry paper which was

shellacked with a persimmon-juice sealant, thus the balloons could survive the 7,500 mile crossing against high altitude winds. The Japanese launched

balloons rose to an altitude which carried the balloons across the Pacific Ocean, allowing them to land in the northeastern part of the United States- and

a few in Canada. These 30-foot wide balloons had bombs attached to them, which were either highly explosive, or were incendiary in nature. The

trigger mechanism was simple but not always effective: a small barometer was set to trigger the release of a few sand bags at a time which kept the

balloons rising and descending as they were cruising across the Pacific at altitudes between 20,000 to 40,000 feet. When all 32 sand bags were

released, the altitude control mechanism took over in releasing the bombs and simultaneously ignited the slow-burning fuses that set off the self-

destruct devices. The balloons were launched by the thousands. Many of them reached the United States, but did not cause the damage which was

anticipated.

The United States learned from this attack that the Japanese balloons used the air currents. Later, the U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command bombers

used this knowledge of air currents on flights to plan attacks on the Russian mainland. The fires started by the balloons, with the added help of

careless campers and lightning, became too much for forest firefighters. What to do? Call the Army, with 400 well-trained paratroopers ready and able

to perform “Operation Firefly”.

The 555th Battalion was ordered westward to Camp Pendleton, Oregon, to begin two weeks training in the proper method of fighting forest fires.

Firefighting, of course, was an entirely new experience. And it was in this field that our new training program began on 22 May. Wills set up one of his

brilliant, loaded training schedules. It was a three week program, which included demolitions training, tree climbing and techniques for descent if we

landed in a tree, handling firefighting equipment, jumping into pocket-sized drop zones studded with rocks and tree stumps, survival in wooded areas,

and extensive first-aid training for injuries - particularly broken bones. We learned to do the opposite of many things we learned and used in normal

jumps - like deliberately landing in trees instead of avoiding them.

We would jump with full gear, including fifty feet of nylon rope for use in lowering ourselves when we landed in a tree. Our steel helmets were replaced

with football helmets with wire mesh face protectors. Covering our jumpsuits and/or standard army fatigues, we sore the air corps fleece-lined flying

jacket and trousers. Gloves were standard equipment, but not worn when jumping: bare hands manipulate shroud lines better.

Naturally, our physical training program was intensified, because missions often found us miles from civilization and in heavily wooded and

mountainous terrain. It paid off handsomely, because few injuries occurred and only on death. On most of our missions we would work with forest

rangers. They were a fine group of men. They could walk up the hills like a cat on a snake walk. They taught us how to climb, use an axe, and what

vegetation to eat. At the same time, we underwent an orientation program with Forest Service maps. And, above all, our morale and spirit of adventure

never sagged in the face of this unusual mission.

On 8 June, we began working with bomb disposal experts of the Ninth Army Service Command, learning the touchy business of handling unexploded

bombs, as well as how to isolate areas in which a bomb, or suspected bomb, was located. Some of us with infantry bomb training, and graduates from

the Parachute Demolition School at Benning, served as assistant instructors. Then came the new parachute. The parachute training was under a

civilian, Frank Derry, who had designed the special chute for jumping in heavily forested areas. A special feature of the so-called “Derry chute” was its

maneuverability. By pulling the white shroud line, the chutist could turn himself into a 360 degree circling movement. This, in turn, gave him a wider

choice of landing areas - a vital factor when trying to avoid tangles with the highest trees in the thickly-timbered areas.

By mid-July, the entire battalion had qualified as “Smokejumpers” - the Army’s first and only airborne firefighters. Soon, our operations would range

over at least seven western states, and in a few instances, southern Canada. And there would be two home bases - one in Pendleton, Oregon, and one

in northern California at the Chico Air Base.

The roar of the propellers brought me back to the job at hand. I looked up and saw the red light had turned to green. The Jump Master gave the order

to jump. We had arrived at our fire. All 34 enlisted men and two officers jumped and assembled on the ground about 500 feet from the burning trees.

We at once established camp and began to work on a fire line. Several enlisted men were injured during the operation. I sent one officer and some

men to carry the wounded down the mountain to a waiting truck. One soldier had a broken leg above the knee and one a crushed chest. They went by

PBY plane to a Tacoma, Washington, hospital.

We had plenty of good luck. It rained very hard off and on for two days and nights, making our job so much easier. The fires cooled down, and three

days after the ground troops arrived, we were relieved of our duties. We prepared to pack up and leave the fire line.

As I looked back at the smoldering fires, I was struck with sudden understanding of my reason for being there. Why would a Black man risk his life to

help his country? The answer was simple. This is my country; this is my duty regardless of the social climate; regardless of the faults. This is my

country, my children’s country and their children’s. It is up to me and many, many people of all races and cultures to fight the haters and racists to make

this a better place to live.

After the war was over, “Operation Firefly” was closed and we became a footnote in World War II history.

We have come a long way since those days of 1945. Since then, we have had a Black General commanding the Army fort that would not permit me to

buy cigarettes in the Post Exchange (while German and Italian prisoners of war could go into the Exchange and buy anything they could afford). We

have had the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretaries of Agriculture, Energy and Commerce, and many other positions of power and trust, all

held by African Americans. We are moving toward a colorless society. We’ve come a long way and we still have a long way to go. With the help of all

people, I have a good feeling about the future of this wonderful country.

For the “Triple Nickles,” it is gratifying to know that many of the techniques and equipment tested and developed during “Operation Firefly” are still in

use in both civilian and military firefighting missions.

Jumping toward equality

Walter Morris and the first all-black paratroop unit blazed trails in the air

By MARY AWOSIKA

It was Feb. 18, 1944, and 16 men stood in formation, dressed in U.S. Army uniforms, chests out and chin up.

The parachute-school instructor placed a paratrooper wing pin on the lapel of each uniform in a ceremony that would

validate 23-year-old Walter Morris' place in the U.S. Army.

Morris and his compatriots were making history, becoming America's first all-black paratrooper battalion, the 555th

Infantry, also known as the Triple Nickles. Due to a family emergency, the 17th member was unable to attend the

ceremony.

Six months earlier, Morris was a guard who, without his commander's permission, had led training sessions to mimic parachute practice after duty

hours to raise the morale of the black soldiers. His actions would land him a position as first sergeant in the test platoon, and open the door for black

soldiers to volunteer for the 555th battalion.

"I can't describe the feeling," Morris said sitting on the pool deck of his home in Palm Coast, north of Daytona Beach. "You had a sense of pride," he

said. The Triple Nickles, a company of 165 men, was activated from 1944 until the end of World War II and on until 1947, breaking the color barrier in

the military. Not since the Buffalo Soldiers, the all-black unit that was formed after the U.S. Civil War, had blacks had such prominent wartime posts. By

the end of World War II, there were more than 400 black paratroopers.

Eighty-five-year-old Morris said his actions proved that black men weren't second-class citizens. He remembers well a time of segregation and

humiliation that today's young soldiers would find hard to imagine.

Even as commissioned Army officers and paratroopers, black soldiers were disrespected, Morris said. He recalled being approached by military police

at a train station in North Carolina.

The MP asked Morris, who was wearing his paratrooper uniform, to show proof of his military status. When his printed orders weren't enough proof,

Morris was arrested for impersonating a paratrooper.

These actions, Morris said, made it "a natural thing for black soldiers to have an inferiority complex."

"In the 1940s, it was easy to ignore blacks' participation in the war," he said. He gestures with his hands, and speaks passionately about social

injustice.

"We were cooks, waiting tables, and loading ship docks and left out of history," he said.

Unlike the Tuskegee Airmen, the well-known black fighter pilots, many people are unaware of the Triple Nickles because the battalion was assigned to

a secret mission: Operation Firefly for the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

As smokejumpers, or airborne firefighters, the Triple Nickles had to minimize the damage from aerial attacks by Japanese balloon bombs over the

Pacific Northwest coast, from Canada to Mexico. Once they made landfall, the 555th Infantry would contain the fire until ground units arrived with water.

"Sometimes it took two to three days because the area on fire could be 25 miles away from the road," Morris said. The battalion completed more than

1,100 individual jumps, fighting 32 fires, some of which were caused by lightning and careless campers.

The Army kept Operation Firefly quiet because they didn't want the Japanese to know that the balloon bombs had actually reached the U.S. coastline,

Morris said.

And he is certain there was another reason: discrimination.

"None of the commanding generals wanted to accept the black battalion because it meant integration, which had never been done," he said.

The Triple Nickles continued its smokejumping mission six months after Germany surrendered, and then was deactivated in 1947. The battalion's

success could not be denied, and Gen. James Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, recommended that the Triple Nickles be integrated

and become the 3rd Battalion of the 505th Infantry Regiment.

This paved the way for black soldiers to become part of the 82nd Airborne Division, one of the most prestigious departments of the Army.

"When you look out at the Army of today, it's such a pleasure because it's such a difference," Morris said. "You see white, black, red, yellow all doing

their job."

Morris was discharged from the Army one year before the Triple Nickles was deactivated and integrated into the 82nd Airborne Division. He left

Georgia and the Army to join his father in Seattle as a bricklayer, moved to New York City and 35 years later he retired to Florida.

He's been active in the Palm Coast community, where he co-founded the African-American Cultural Association, an education facility for adults and

children. As a member of the Tampa-based 555th Parachute Infantry Association, Morris keeps track of his friends, traveling for national Triple Nickles

reunions and chapter functions.

The association, established in 1979, is a way to ensure the legacy of the Triple Nickles, said Joe Murchison of Tampa, the president and organization

co-founder.

"When the 555th was folded into the 505th and changed the name, it was an end of an era for the men who were involved," Murchison said.

Currently, there are 1,000 members and 28 Triple Nickle chapters, two in Florida. Murchison is planning the 2006 reunion in Fort Leavenworth, Kan., on

Labor Day weekend.

"Without that first group, led by Walter Morris, there would have been no Triple Nickles," Murchison said in a phone call from Tampa.

Morris said he's flattered by remarks such as Murchison's that suggest he influenced the test platoon.

As far as he's concerned, he was just doing his job.

Two years ago, 50 years after receiving his own wings, Morris returned to Fort Benning to witness his grandson Michael Fowles' graduation from

paratrooper school.

In stark contrast to Morris' class of 17, Fowles' class was 400 strong. Morris was the honorary speaker, but it was his grandson who said he was most

proud.

"I felt a closeness with him that I will always cherish," Fowles said from his office in Fort Jackson, S.C. He's a captain and battalion operations officer.

"At the same time, there's a great responsibility on my shoulders. I have to represent him well ... with dignity and respect."

“We as colored soldiers in Ft

Benning could not go into

the main Post Exchange. We

looked in [and] could see

German and Italian prisoners

of war sitting down at the

same table with white

soldiers…. So it is

understandable how colored

soldiers would have an

inferiority complex.”

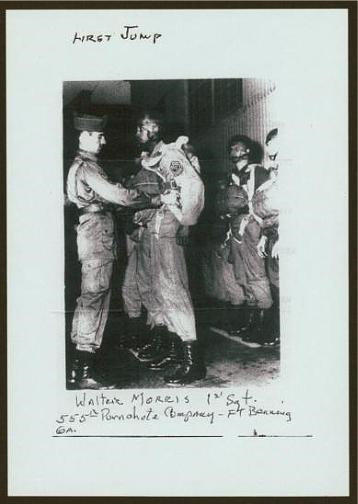

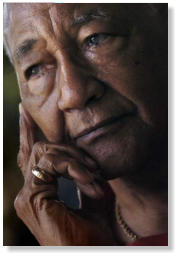

Pictured above: Walter Morris, a retired 1st sergeant, was an

original member of the Triple Nickles and the first enlisted

black man accepted for airborne duty in the U.S. Army. He's

shown with his family Thursday, Sept. 7, at Fort Leavenworth,

where a statue was dedicated honoring members of Morris'

555th Parachute Infantry Battallion.

Photo by Tricia Masenthin

Pictured below: Walter Morris, an original member of

the Triple Nickles, signs an autograph Thursday, Sept.

7, at Fort Leavenworth, where a statue was dedicated

honoring members of the 555th Parachute Infantry

Battallion.

Photo by Tricia Masenthin