© Official Site Of 555th Parachute Infantry “Triple Nickle”. 2008

"Tomorrow, the class will tell us about their ancestors and their fathers. The

teacher said, "We don’t have to tell about ours" remarked my daughter Charris,

in response to my question. We had just completed our dinner’s prayer, when I

asked how school was today. Further discussion revealed that the African-

American students were not to participate, because of the lack of availability of

information concerning their ancestors. At this point and for the next several

weeks I started telling them about their ancestors.

First, I began explaining to them about my grandfather, Gush Beavers, who was

born in 1833 and my grandmother America who was a Native American. She

had one son (my father), Tipp G. Beavers, Sr. who was born on February 16,

1879, in Talladega, Alabama. I also told them about my mother, Mary E. Martin-

Beavers who was born in 1881 and her father, Samuel Martin, who was born in

1845, and mother Sarah Nell who was born in 1858, both previously escaped

from being enslaved on the Martin Plantation. Samuel Martin also was a veteran

of the Civil War with service in Company I, 50th Infantry Regiment (Colored)

United States Army. Upon his being honourably discharged from the U.S. Army

on March 12, 1866, together they had sons and daughters of which my mother

was the first child. I was born on June 12, 1921 at West 134 Street, New York,

New York. And was the 15th child of the 16 sons and daughters given birth to by

my parents, and was named Clarence Hylan, after the mayor of New York City,

who was my Godfather.

My father, Tipp G. Beavers, Sr., worked as a commercial artist for Ringing

Brother Circus. It was Ringling Brothers who helped my father and his family escape to New York City, after my father led a

group to the defence of Talladega College to prevent it from being burned by the KKK. Arriving in New York, his profession was

in great need and it was then that my rearing was guided by a nanny, a retired school teacher by the name of Ms. Wood. She

showed me every museum, and historical site in New York. I even remembered seeing the parade greeting Lindberg on his

return from Paris. This was all to end soon, as the 1929 stock market crash changed the financial status for many, my father

included, and my parent’s family history.

I attended Public School 5, located between 140th Street and 141st Street on Edgecombe Avenue, from the first grade to the

sixth grade. Edwin W. Stith Junior High School and George Washington High School. During the sixth grade, I worked after

school for a blind man at his newsstand and held many jobs during this period such as clerk in grocery store, candy store and

worked in the Garment District to name a few. I explained that at the age of 18, I enlisted in the 369th Infantry Regiment, New

York State National Guard and served under Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis Sr. During the summer of 1940, I received

my release from the 369th Infantry as my time was needed managing my restaurant.

When Dawn raised the question of how I had gotten into the army, I explained that during 1941 I was drafted for service and on

March 13, 1941 was bused over to Fort Dix, NJ and was assigned as a training Sergeant. On an untimely trip to New York, I

stayed over the weekend which resulted in me being placed on orders to Camp Lee, VA, which had just reopened. As a platoon

Sergeant in the 9th Quartermaster Training Regiment I earned $21.00 for 90 days and $60.00 monthly thereafter. In the 9th

Quartermaster Training Regiment, remaining, I was a Drill Sgt. for the next 9 months. Rather than going overseas as a 1st Sgt.

in a Transportation Regiment, I accepted an assignment to a Light Ordnance Maintenance Platoon at Indiantown Gap,

Pennsylvania.

Well, the question came back, how did you get into the paratroopers asked Patricia? In early part of 1943 the unit received

overseas orders, at the same time a War Department Circular was also received seeking volunteers (Army IQ above 90, mine

was 110) for jump training. My application with my physical was approved and War Department orders were received removing

me from any pending overseas order and ordering me to report to the Parachute School, at Fort Benning for Jump Training. I

explained that during the middle part of World War II, African Americans were token to the personnel serving in all elements of

the US Army, except in the parachute units and/or airborne elements. The President of the United States, Franklin D.

Roosevelt, appointed the McCloy Advisory Committee which included Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. to review and

make recommendations concerning special personnel (African Americans) in the U.S. Forces. Included in their December 1942

recommendation to the President was that African American units be accepted into combat duty previously restricted to whites

and the starting of an African American parachute Battalion. In February 1943 the Army Chief of Staff General George C.

Marshall, disregarding the McCloy committee recommendations, wrote on the cover letter “Start a Company”. Yes this was

tokenism, again.

The next question was, how did you become a paratrooper asked Charlayne? I took them back to an evening in March 1943.

That evening the train would reach Columbus, Georgia. Columbus is a small town near The Parachute School, at Fort Benning.

It had been a long ride from Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. Sitting in the first passenger car of a train heading south, watching

the homes along the railroad tracks, I soon noticed that the houses were like those in Virginia. Mostly run-down and people

living in them were mostly African-Americans. And there were signs placed up saying, “For Whites Only” and others saying "For

Colored." We were hopeful that if we did a damn good job, things for the African Americans would improve after the war had

ended. Riding to Parachute School, the driver of the Jeep sent to pick me up kept looking at me as we passed each street light.

Under the fear of him having an accident, I told him I was a Negro and requested that he keep his eyes on the road and his

mind on driving. Upon reporting to the Officer of the Day, I was to be quartered at an African American billet for the night.

The question was “Are you now going to be a paratrooper” asked Charlotta? I explained that the next morning I was escorted by

Major General (then Colonel) H. J. Jablonsky, to meet with Brigadier General Ridgely Gaither. He remarked ‘If the Department

of the Army wants us to train him as a Paratrooper, then we will train him as a paratrooper. Put him in the class starting this

morning.” This order was gratefully received by me. However the feeling of great proudness, pride and joy of going to jump

school I felt was short lived. The Assistant Commandant asked, "What are we going to do with him after we train him?" He then

suggested to General Gaither that the Department of the Army be informed that orders assigning me were premature, as there

was no colored unit to assign me to, after completing training. "This was one of the most depressing days of my life, both then

and now. I had to stand there not only to hear these field grade officers of the U. S. Army, refuse to train me as a paratrooper,

not because they thought I would not make a good paratrooper, because the feeling in the room that day was I would qualify,

and win my jump wings, but because I was an African American I could not be trained. This was borne out by the remark "After

he completes his training - where would we assign him?” The only reason I was being refused paratrooper training was because

of the color of my skin. “Something that I had always felt proud of they were trying to make me feel ashamed of." I was to be

assigned for rations and quarters, to Service Company (colored), an African American unit performing guard duty around the

Parachute School. With help of the Commanding Officer of Service Company, (A former Paratrooper Captain who’s

misbehavior had resulted in him being assigned as Commanding Officer, of African American enlisted men), I wrote a letter to

the Department of the Army, through channels, concerning the Parachute School’s failure to comply with the issued orders.

Around late summer or early fall the letter was returned with a blank endorsement indicating it reached the office of the Army

Chief of Staff. But it was not until December 30, 1943, that an African American paratrooper unit would actually become a

reality. I remained assigned there until I completed my jump training and was transferred in February 1944 to the 555th

Parachute Infantry Company.

Daddy are you now going to be a paratrooper asked Clarence II? In the winter of 1943, orders were received from the

Department of Army to train Colored (Blacks/African Americans) personnel as Paratroopers. At that time I was the only African

American person in the US Army who had volunteered, been accepted and transferred on orders to the Parachute School for

Jump Training. During the first week in January, 1944, we started our four weeks course of jump training. The plan being we

(two enlisted men for the Service Company, seventeen from 92nd Infantry Division at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, who were

assigned to the Parachute Infantry Company on December 30th & 31st of 1943 and I from the Parachute School) were the

African American Test Platoon. Upon completion (if we completed??????) of our training we would train the officers and the

next group of enlisted men for the 555th Parachute Infantry Company.

During our training, which I explained was extremely rough and extremely personal, three members washed out. We trained,

ate, were housed and made our five jumps as a separate unit. If I remember correctly we had four white training instructors,

who had volunteered for the job. Those that wanted to see us make it put forth their full effort; equally those who didn’t want to

see us to make did everything they could to see that we didn’t. I explained to them, while other trainees came though the front

door and went to counter for their food, we had to come in by the side door and go right to the first table on our left. We

were not allowed to go to the counter but rather were served our food and were to leave by the same door upon completing

eating. Our quarters were huts off from the other quarters, without heat, a building far too small for twenty men. Some of this

ended up helping us through our training, like being served at a table was great after extremely rough days of training and the

smallness of the hut, and body heat of men tended to warm the hut. We were told some instructors were heavily betting on

whether we would jump or not. The Signal Corp. took pictures and movies of our training for Africa-American newspapers and

theatres across the nation.

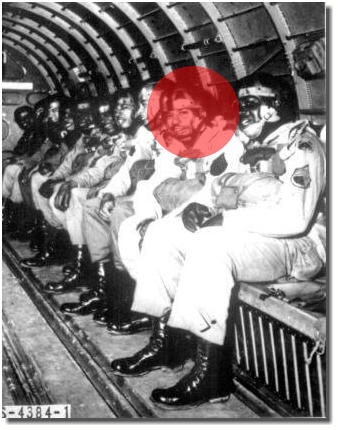

The question was, “Were you a paratrooper yet” - asked Charris? On Monday, January 24, 1944, we, the African American’s

Test Platoon (sixteen of us) sat on the first row of seats in the sweat-shed with parachutes on awaiting the C-47 to take us for

our first jump. As a spotter plane was flying beside us again taking pictures as we made our initial 5 jumps. The jump order was

as follows Calvin R. Beal, Clarence H. Beavers, Ned B. Bess, Hubert Bridges, Lonnie M. Duke, McKinley Godfrey, Jr., Robert F.

Greene, James E. Kornegay, Alvin L. Moon, Walter J. Morris (first African-American assigned to the 555th Parachute Infantry

Company), Leo D. Reed, Samuel W. Robinson, Jack D. Tillis, Roger S. Walden, Daniel C. Weil and Elijah Wesby. I explained to

them, that before his death, I received a letter from the late Maj. Gen. H. J. Jablonsky USA. General Jablonsky was the

Assistant Commandant for Training at the Parachute School, Fort Benning, during our jump training. In his letter he remarked,

and I quote: "They were a great group of soldiers and we trained them with a loss of only 3.” During "D" stage which is jump

week, we were visited by a senior black officer, Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis of the Inspector General’s Office. This

grand old white-haired officer had been commissioned in the Spanish-American War, retired and was then recalled to active

duty for WWII. He wanted to see the black cadre jump so we boarded a C-47 jump plane where he watched the trainees make

their third of 5 qualifying jumps. After we landed, General Davis turned to me and said, "Colonel, what is the minimum size

parachute unit the War Department contemplates using in combat?" I replied that to the best of my knowledge that it would be a

battalion size. He then asked, "Then why are you training a cadre for a company size unit of black parachutists?" I replied "That

is all the War Department sent us."

Within 30 days, we received orders to train enough blacks to fill a battalion which we accomplished in the spring of 1944. This

became the 555th Parachute Battalion, later called the Triple Nickle. In my opinion, General Davis was the father of the 555th. I

am not sure your association has this early historical information. The above is as I remembered it. Dates are a bit hazy.

Unquote.

Due to poor jump weather on both Friday and Saturday nights the night jump was made on Monday night, February 8, 1944,

Brigadier General Ridgely Gaither, The Commander of the Airborne Command, presented parachute wings to us,

(Paratroopers), the first African American Military Personnel to have completed training. Being proud and confident men, we

became the first African American Paratroopers in the Army. "Thus winning respect of others and money for those who had bet

on us!"